Knowledge is realizing that the street is one-way, wisdom is looking both directions anyway.

People call me Lizzie Bee

People call me Lizzie Bee. Southern California is where i call home and I have a family that I wouldn't trade for anything. Taken By A Good Man. Life is too short to not enjoy the beauty, comedy, sadness, love and righteousness that it holds. So here I share the things that mean something to me, in hopes they will mean something to you as well. Like OrangeSUnshine Blog on FACEBOOK for streaming updates: facebook.com/OrangeSUnshineBlog

Thursday, September 29, 2011

Wednesday, September 28, 2011

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Calling Your Ex

Calling Your Ex 65,000 Times Is 64,999 Calls Too Many

Posted by Lindsay Mannering on September 8, 2011 at 4:48 PM

Since we're all friends here, I think each of us can admit to an unadvised call to the ex every now and again. It goes something like: You're feeling a little lonely, it's late at night, and that box of wine you gulped down with your frozen dinner has gone straight to your head. After cleaning out your cat's litter box, pooper scooper in hand, you think, Oh, what will one call hurt. He won't pick up anyway. And if he does, it's like, meant to be. Let me just see if I remember his numb ... [dials fervently, and correctly.]

We've all been there. And we've all realized, after getting his voicemail, that we're crazy and vowed to never, ever allow ourselves to call him again. Most of us stick to that goal. A woman in Denmark didn't. She called her ex 65,000 times in one year, and is facing charges for being the bat-shittiest lady on the face of planet earth.

Let's do some quick math. If she called him 65,000 times in a year, that's 178 calls a day. She's awake about 16 of those hours ... carry the one ... she must have called him roughly 11 times an hour, every hour, every day, for a whole year.

Understandably, the man was a little, say, annoyed. Why he didn't change his number after the first week is one of life's greatest mysteries, but he did call the police. The woman has been ordered to stop contacting her ex. Well, she says he's her ex ... the man says they've never had a relationship.

Lest you think these were some horned up teens, let me tell you that the woman is 42 years old and the man is in his 60s.

Let's see if the woman adheres to the court order -- something tells me that if she's persistent enough to make 178 calls a day, 365 days a year, she's not going to be dissuaded easily. Her cell bill has got to be crazy high.

I guess we can all walk away from this story knowing that we're not the craziest people out there -- that there's someone with a few more screws loose than us. Yay! God bless that insane Dane.

This had me cracking up. Original article and site can be found HERE.

Clouds Photographed from Open Airplane

See more photos and a video of the adventure HERE.

Wire Sculptures

Incredible wire sculpture art by French Artist Gavin Worth. You can see more of his work HERE. It reminded me of some wire figuring I had seen in Ocean Beach, San Diego a few years back. Intriguing because of how simple, yet detailed these types of work can be.

Wire Sculpture by unknown artist.

Monday, September 26, 2011

Thursday, September 22, 2011

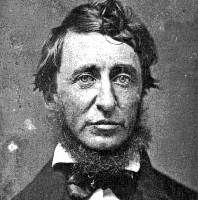

Why Walden matters now... Boston.com

Today on Boston.com

Why Walden matters now

|

ON SATURDAY, I’ll be walking with friends to Walden Pond, six miles from where I live in Wayland. From there we’ll head to the MBTA station and take the commuter rail (the same Fitchburg line Henry Thoreau knew) to Boston, to join the Moving Planet rally at Columbus Park and call for the world’s leaders to get serious about moving beyond fossil fuels.

Ah, Walden, you’re thinking, of course. Environmentalism. Thoreau. Walden Woods. Don Henley. Right on.

Actually, wrong. Or I should say, only partly right. I’ll be walking to Walden because, like the writings that made it famous, this is about far more than environmentalism. It’s about humanity.

Henry David Thoreau’s great subject - in “Walden’’ and “Civil Disobedience’’ and just about everything he wrote - wasn’t the environment (a term he wouldn’t recognize) or even nature (though he was a first-rate naturalist). It was “Nature,’’ as he wrote in “Walking’’ and “man as an inhabitant, or part and parcel of Nature.’’ It was our relationship, as human beings - physically, morally, spiritually, politically - to the world in which we live, which is to say, to everything, both human and wild.

Thoreau was not an “environmental’’ writer but a deeply human, moral, and spiritual writer - and a deeply political one. And he knew that on the most pressing moral questions, the spiritual and political can, and often must, go hand in hand - a conviction shared by one of Thoreau’s 20th-century readers, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

There’s also a popular misconception that Thoreau was a hermit or recluse, indulging a utopian fantasy in his refuge in the woods. Thoreau’s cabin at Walden was no retreat from the world. He had an active social life at the pond, but more to the point, he was socially and politically engaged.

In fact if anyone took refuge in that cabin, it was the runaway slave Thoreau sheltered along the Underground Railroad. Thoreau’s antislavery activism, in words and actions, needs to be remembered as central to his legacy. For Thoreau, to be morally awake and in harmony with nature meant to act on behalf of human freedom.

In May 1854, as Thoreau was putting his final touches on “Walden,’’ another runaway slave named Anthony Burns was arrested in Boston. A riotous crowd, led by abolitionist friends of Thoreau’s, tried to free Burns from the city’s courthouse, but Burns was sent back to the South after federal troops intervened.

On July 4, at a rally in Framingham, Thoreau delivered the fiery abolitionist speech called “Slavery in Massachusetts’’ and indicted the Commonwealth for its complicity in human bondage. His sense of serenity in nature was shaken: “I walk toward one of our ponds but what signifies the beauty of nature when men are base?. . . Who can be serene in a country where both the rulers and the ruled are without principle? The remembrance of my country spoils my walk.’’

But did it spoil the walk, or reveal its purpose? Thoreau’s immersion in nature, and his spiritual awakening there, led him back to society and its reform.

There is no greater threat to human freedom today than climate change. If slavery was the human, moral crisis of Thoreau’s time, then global warming - and its impact on countless innocent lives - is the human, moral crisis of our own. We know that our burning of fossil fuels is global warming’s major cause, with vast and potentially catastrophic consequences for future generations, including our own children.

As Thoreau knew, in the face of such facts the thing to do is not retreat, but engage.

There’s still time to preserve a livable planet for our children. But we need more than small gestures of personal green virtue. We need decisive government action - which means a political movement that transcends “environmentalism.’’ Because the climate crisis is more than an environmental crisis, it’s a human crisis, and we need a new politics to address it on those terms.

That may sound hopeless, especially now. But then, abolishing slavery sounded hopeless in 1854 - as Henry David Thoreau no doubt knew.

Wen Stephenson is a former editor of the Globe’s Ideas section.

© Copyright 2011 Globe Newspaper Company.

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

Monday, September 19, 2011

Friday, September 16, 2011

Thursday, September 15, 2011

Wednesday, September 14, 2011

The Illustrated Man

"You see, you have no mental evidence. That's what i want, a mental evidence i can feel. I don't want physical evidence, proof you have to go out and drag in. I want evidence that you can carry in your mind and always touch and smell and feel. But there's no way to do that. In order to believe in a thing, you've got to carry it with you. You can't carry the earth, or a man, in your pocket. I want a way to do that, carry things with me always, so i can believe in them. How clumsy to have to go to all the trouble of going out and bringing something terribly physical to prove something. I hate physical things because they can be left behind and become impossible to believe in."

-Ray Bradbury

Tuesday, September 13, 2011

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)